Biella, it’s Tuesday 28th January, the day is turning to dusk. From the office window I glimpse at the night overcoming the day, despite the pleasant weather of the previous hours. Eyes stuck to the PC, hands on the keyboard, my fingers are running fast. Absorbed in my writing, I see Paolo Naldini, the director, just popped in for a quick exchange with a colleague. While he leaves in a hurry, given how busy he always is, he tells me that a Rebirth/Third Paradise ambassador, Davide Carnevale, and an Ethiopian artist are about to arrive at Cittadellarte. He doesn’t add much, but he invites me to meet them. I think that, who knows, an interesting story for our Journal might come out of it, so I write to Davide and we arrange to get together the following morning.

The day after, I meet them. He says hi with his usual warmth and she demurely introduces herself. We head for the meeting room, I’m curious to know what has brought them to the Foundation.

Davide, whom I’ve known for years having more than once talked about his commitment to the Third Paradise project, is very enthusiastic, excited, almost proud of what he is going to say. Alem Tekly Kidanu, this is the name of the 43-year-old artist accompanying him, is patiently waiting for her turn to speak. This is not common: most times who is here to share their own story has a certain involuntary urgency to reveal every detail as fast as possible, in a sort of frenzy. Like when we find ourselves in front of food we really like and greed overcomes good manners.

Alem Teklu Kidanu.

But that’s not the case with her. She patiently waits accepting the fact that Davide is talking instead of her. It’s not a prevarication, but a sign of her total trust in him. The ambassador introduces Alem, mentioning her origins (she is from North Ethiopia, from the Tigray region, but now lives in Carrara), her artistic practice and her story. But I can’t go too far into her life, I must first of all understand how they met and why an Ethiopian and a Campanian artist are here at Cittadellarte. This is when Alem starts speaking, revealing what was the occasion that brought them together. As in a novel, their lives crossed by chance, or almost: “About a year ago, one morning, two friends, knowing my interests and skills in the artistic field, suggested I should meet Davide. That same afternoon, while out with them on a walk along the shore of the Averno lake, we met him without having arranged it. Fate wove the threads of our meeting”. They have been in sync from the start, not only because of their shared passion, but also because of their common way of intending it. The spark kept growing in the following weeks, to the point where Alem participated in Davide’s land art project developed at the Phlegraean Fields in Pozzuoli, west of Naples.

Alem and Davide busy with the land art project at the Phlegraean Fields

The ambassador anticipates the dream of the artist colleague, which struck him deeply: all Alem’s practices are centred on one objective: creating an art school in Ethiopia. “In my country – says Alem – women don’t have access to education, they are forced to lead a domestic life. I, instead, have proved that we too can build our own future through school, and I have personally found out that in Italy this is possible”. Davide speaks out again: “That’s it Luca, you see? All the parallelisms with the Third Paradise… change can be triggered through art, we once again want to show that”. The ambassador goes on to reveal the behind-the-scene of the artistic project he is developing. Why have you decided to help Alem fulfil this dream? “Because I realised that, at last, I was given an opportunity to not only exercise the theory of demopraxy, but also practice it. This is one of the keywords common to all the projects I develop on the territory, which are mainly limited to a local dimension. While here, instead, I have the chance to commit to an objective in line with mine and with the precepts of the Third Paradise, in a context where change is even more urgent”. Davide has therefore started collecting data to achieve this objective, at first studying the dynamics of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation in the African countries, then gathering information to be able to present a concrete project proposal. Throughout this process, Davide specifies, it’s essential to think about how to involve other actors and organisations that can profit from participating: “A dream – adds the ambassador – must become a need to become reality”.

Once the goal was set, the path to get there had to be built. And in this case too art able to trigger a responsible social transformation has been the leitmotiv of the building process. Why? One of the fundamental pieces to complete this puzzle is money, but the two artists have decided to ask for help without standing still. How to get financial support? No fundraising campaigns, no passive donations. But art, yet again, tinted by theatre. “Alem – Davide explains – is also an actress. And she has been touring Italy with a play called Miraggi Migranti (Migrant mirages), centred, as the title suggests, on the journeys of the migrants. We would like to collect part of the funds needed for the project of the school through a new theatre performance dedicated to her story. The other approach will be to ask the ambassadors of the Third Paradise for advice and contributions, to understand if our promotional concept could apply to other territories. We want to rely on the demopractic method to reach our goal, and we have therefore met with Paolo Naldini to examine the possibility of a partnership with Cittadellarte”.

The idea is clear, and apparently functional: it constitutes an artistic contribution, at the same time offering a glimpse into a cross section of a reality geographically far from us. The play focuses in fact on Alem’s past and conveys a message through art; the spectator can therefore become a first actor of change, deciding to financially support the project. Alem’s story is not an individual experience, it reflects lives fraught with difficulties typical of many of her fellow citizens. And when we touch on that issue the Ethiopian artist’s expression changes: her face saddens, her mind suddenly pervaded by terrible memories. But she doesn’t give in to her past fears, she actually seems to draw strength from this darkness. “One of the biggest problems troubling my country is illusion. People – she says – think that leaving for Europe, America or other parts of the world means getting rich, changing life, defeating poverty. I myself left home at some point, to go to Arabia. I thought that’d be a new beginning, but I ran the risk of being exploited instead. I was lucky enough to be able to run away”. After this escape, a new phase of her life actually started, between Ethiopia and Italy, which eventually saw her passion for art thrive with a degree from the Carrara Academy, where she learnt different techniques specialising in marble plastering to produce sculptures and bas-reliefs.

Is that the light at the end of the tunnel? Not quite. Because in spite of the important achievement of a degree, her family was not pleased with her. Art, this stranger. And the coveted Italian wealth, still nothing. “As I mentioned – Alem goes back to the issue of social illusion – in Ethiopia people have the wrong idea about travelling to Europe. There is the perception, or even the conviction, that by moving elsewhere you can easily change life. But it’s an illusion. And that’s how we become victims of systems that don’t work. I’m not saying that coming to Italy is wrong, but simply that it’s important to know what you are going to be facing”. Someone feeds this illusion. And finding out who is responsible for that is a (sad) twist: “The immigrants themselves are the ones communicating lies. They show off a wealth they don’t actually have, but it’s not their fault. When they leave for Europe or America they are cherished by their families, who are proud of them, the journey gives them prestige. If you just think about the fact that it’s extremely difficult to get help to start a project in Ethiopia, but everybody finds the means to leave, because they believe that some day their life will change as a consequence”.

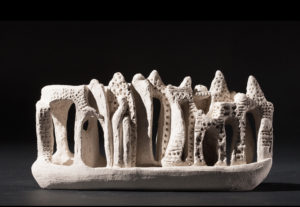

A few of Alem’s works.

Alem even tells us that in the villages it’s tradition to celebrate, almost ritually, their departure. “After all that – she continues – you reach your destination and… there’s nothing there. Not only for your friends, family, village, but for you either! Most times you start your new life without documents. And often it’s not the homeless that undertake this journey, but people with degrees, with an education. But when they get to their destination, when they understand the real situation, they are ashamed. They can’t accept it and tell the truth. Therefore everything implodes”.

Fabrizio De André, in his famous song Il cantico dei drogati (The drug addict’s song) used to sing “How could I tell my mother I’m scared?”. That’s it. How do you admit to such a failure? How do you overcome the shame of a failure? This is what triggers the lies.

And the truth is what Alem wants to tell, through her play Miraggi migranti. “I don’t want to have gold to show off wealth. I want to take culture to my country”. At the beginning, as you can imagine, it hasn’t been easy: “People wouldn’t believe my words but art – through my theatre performance – has managed to convey reality”. The turning point, at a personal level, was when her family assisted to her theatre show and, on the occasion, her mother was interviewed by CNN. During the interview, her mum publicly apologised for never appreciating that through art Alem was offering her community a high value of female dignity. “At that moment I understood that I was on the right track. My friends and brothers are now supporting me, and at last many other people believe the truth I tell”.

Miraggi Migranti, a figure theatre play on the journey of the migrants (it had its debut in 2013 at Mekelle university). The performance is addressed to secondary school students.

Buda – stories of a migrant artist, a work about Alem’s life written for high school students and adults.

Miraggi Migranti involves Alem as actress, Soledad Nicolazzi as director and Alessandra D’Aietti as the composer of the music especially created for the stage performance of Compagnia Stradevarie (Campsirago Residenza). The same group of people is behind the new play Buda – stories of a migrant artist, focusing on Alem’s personal experience. The Ethiopian artist also makes both the costumes and the papier-mâché masks used for the performance. Her artistic skills are contributing to the first play too, which is structured as a tale narrated through mime: “The miming language – she says – is universal and allows us to be understood by any spectator”. After carefully listening to our conversation, Davide concludes by saying: “Alem has already triggered a process of change, but she wants to generate a more powerful one. How? Through the dream of the school”.

We say goodbye with the promise to catch up on the development of the project further on. I thank her for donating me her story. I am convinced: she will make it again, her art will overcome everything. That school will be created.