Arte Povera has bid its farewell to its founder: two days ago, at the age of 80, Germano Celant passed away. A curator and art historian, he lost his battle against the Coronavirus after two months in the ICU of the San Raffaele Hospital in Milan, also due to following complications. A sad day for the global world of art, mourning one of the icons of the movement arisen in the second half of the 1960s. “Essentially, Arte Povera manifests itself in reducing to the minimum terms, in impoverishing the signs, to reduce them to their archetypes”. This is how Celant presented the movement begun to oppose traditional and consumerist art.

But associating Celant only with Arte Povera would be reductive: besides working on publications, essays and catalogues about single artists, in 1977 he started collaborating with the Guggenheim Museum in New York, eventually as senior curator; in 1996 he curated the first edition of the Florence Art and Fashion Biennale; in 1997 he was nominated director of the 47th Venice Art Biennale; he was director of Fondazione Prada in Milan and curator of Fondazione Vedova in Venice; he organised the exhibition ‘Art & Food’ at Triennale di Milano on the occasion on Expo 2015. He dedicated his whole life to art.

Along his professional career, he had a long-standing relationship with Michelangelo Pistoletto, gone beyond work to become a brotherly friendship. Two days ago, on the spur of the moment, Pistoletto expressed his condolences for the death of Celant. “This is the end of a long road travelled together, which was in fact still continuing with new projects. The sadness is overwhelming. To his wife Paris and their son Argento, we are sharing in your sorrow with love and friendship. Together with Maria, Cristina, Armona, Pietra and the whole of Cittadellarte”. Today, two days after the sad event, we are talking with Pistoletto, reliving with him that road they travelled together for most of their lives, around art.

After a long journey together, two days ago you had to part. What’s your memory of Celant as a man and a curator?

My memory of him is of an extremely concrete person in the way he operated, as well as responsive and sensitive in his perception. Pragmatism and sensitivity, two qualities I believe we shared, sealed our relationship. We often united our capabilities, reaching an understanding in the most diverse situations. For me, his demise represents the loss of a person very close to me, something almost unthinkable.

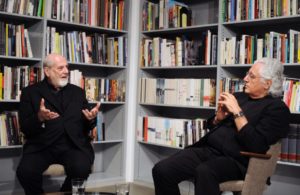

Pistoletto and Celant pictured in Cittadellarte’s courtyard in 2011 (Celant was visiting professor on the occasion of the 2010 UNIDEE in Residence module). Photo credits: https://margavp.wordpress.com/2011/07/03/artists-in-black/.

You met Germano between the end of ’65 and the beginning of ’66, in your studio, while you were working at your ‘Minus Objects’. How was your first meeting?

Celant looked for me and came to see me in my studio in Turin from Genoa. He assisted in person to the process and the activities I was carrying out with the ‘Minus Objects’.

From the very outset of the movement, Celant always recognised you as a forerunner of Arte Povera with reference to your ‘Minus Objects’. How important to you was this consideration, at the time?

I was very interested in the fact that Italy was developing an artistic movement representing a profound change from the great popularity and success of American art, with which I had actually ‘associated’ myself, having been included in the Pop Art genre. Despite the interest and the sense of participation I felt towards Pop Art artists, I had realised, though, that they identified with the American consumerist system, which had taken hold of art, and art had adhered to that system.

I therefore understood that although my work shared the objectivity of the Pop Art artists, its objectivity was detached, not at all linked to the consumerist system. Unfortunately, though, that system led my own work to identify with the commercial process that considered it as a brand, and therefore destined to consumption. As a consequence, I decided to move to the next phase, in which art assumed autonomy and responsibility, thus avoiding being exploited. And I thought that a movement could be developed in this direction. Germano and I talked a lot about these issues… the ‘Minus Objects’, for example, are all different, which prevents the artist from being branded according to a consistent personal style.

Dividing myself in many diverse moments and works stopped the speculation on a personal identity. Other artists then followed suit and gradually, first in Turin and then elsewhere in Italy, started creating works of extraordinary radicalness. That was the beginning of a new relationship between art and reality, even physiological, of what exists. That way, art concentrated on a true connection between essence and consistence. Celant clearly read the process in progress in Italy, and was able to provide a name and a synthetic interpretation for our activity, turning it into a movement.

The 1968 exhibition ‘Arte Povera + Azioni Povere’ was instrumental in the popularisation of Arte Povera. Besides Celant, other artistic figures of great relevance were involved in it. Was that the moment the movement achieved international status?

Celant had already published a book on Arte Povera in 1967. After it had come out, a few galleries like Sperone and Stein in Turin, de’ Foscherari in Bologna, L’Attico in Rome and La Bertesca in Genoa organised a series of exhibitions with the artists representing this new trend. The 1967 exhibition ‘Fuoco Immagine Acqua Terra’, in Rome, already included many artists who would be part of Arte Povera; this goes to show how authentic the developing phenomenon was and how it was perceived on the Italian artistic scene. Germano had the great intuition of giving this movement a name and a theoretical text.

Then in 1968, with the exhibition ‘Arte Povera + Azioni Povere’, in Amalfi, the movement gained official acknowledgement: it was an extraordinary event because, while the exhibition was on, the Venice Biennale was opposed and closed. ‘Arte Povera + Azioni Povere’ was the only alternative to the Biennale, which turned it into a really important affair. The exhibition project also involved a few artists from around the world who somehow identified their work as Arte Povera, the movement had therefore spread at international level. Besides Celant, many Italian critics participated in it. I took part not only with works, but also with actions performed by the Zoo, the group I had founded.

Picture taken in the course of the exhibition ‘Arte Povera + Azioni Povere’, held in Amalfi in November 1968. Visible in the middle is Michelangelo Pistoletto with on his left Germano Celant and on his right the critic Henry Martin, who had taken part in the action ‘L’uomo ammaestrato’ (The trained man), performed by the Zoo, Pistoletto’s group. In the picture is also Piero Gilardi, another of the protagonists of Arte Povera. Photo credits: Marotta.

In the 1970s and 1980s, numerous were the occasions when your paths intertwined: Celant curated your retrospective (and relative catalogue) at Palazzo Grassi on the occasion of the Venice Biennale in 1976; and he did the same for the exhibition Michelangelo Pistoletto at Forte di Belvedere in 1984 and for your exhibition at PS1 in New York in 1988. How important were these stages in your artistic chronicle?

The fact the Germano kept following my work, writing and talking about it, participating in crucial moments like my exhibitions means that our relationship was very close. And not only that: it means that his interest in my work and my interest in his vision of my work coincided.

Michelangelo Pistoletto and Germano Celant. Picture taken at the Luhring Augustine Gallery in New York on the occasion of the 2013 exhibition ‘Michelangelo Pistoletto. The Minus Object 1965-1966’. Photo credits: Pierluigi Di Pietro.

Let’s now talk about the recent past: an absolutely seminal moment was the 2017 exhibition project ‘Ileana Sonnabend and Arte Povera’ at the Levy Gorvy Gallery in New York, for which Celant retraced and rebuilt the works of Arte Povera artists from the 1960s with reference to the activity of the naturalised American art dealer from Romania. What was the importance of that event?

Ileana Sonnabend played a fundamental role in my career as – starting from 1963 – she acknowledged, presented and publicised my work; in 1967 she then began dealing with Arte Povera artists. I can therefore claim of having been the first to establish a relationship with this gallery, an American institution with an international vision. Ileana, with her interest in Arte Povera, showed her cultural and artistic open-mindedness.

I was invited, with Germano Celant, to present the exhibition ‘Ileana Sonnabend and Arte Povera’ at the opening event. Germano and I therefore met there to describe the events that led to the creation of the Sonnabend collection, at the same time recounting the journey we shared. The Levy Gorvy Gallery was supposed to be hosting one of my exhibitions right now, which had to be postponed due to the restrictions imposed to contain the spreading of the Coronavirus. I can anticipate that it will have a close connection with the Sonnabend collection: but if the 2017 exhibition looked to the past, this one will be inspired by the future.

Ten years ago, in 2010, Celant was invited to Cittadellarte as visiting professor on the occasion of a UNIDEE in Residence module. Why was he chosen for this role?

His presence as an art historian could highly contribute to the understanding of late 20th century art, in connection with what we do at Cittadellarte (responsible social transformation through art). His participation was therefore essential, also because he could bring important perspectives on art at international level, given that he had eventually developed his activity in the Unites States.

Celant in Cittadellarte’s courtyard giving a lesson during a ‘UNIDEE in Residence’ module in July 2010. Photo credits: Margarita Vasquez Ponte.

Michelangelo, your Third Paradise is a harmonic synthesis of two opposites: you often illustrate this process referring to binomial pairs like man/woman, positive/negative pole, nature/artifice, just to mention a few. Let’s now consider one of the key words characterising your artistic practice, i.e. ‘rebirth’. What role does this notion assume in the face of death? Are rebirth and death strictly linked, or are they in the two opposite circles of your sign-symbol?

In the concept of the Third Paradise, birth and death are the two points delimiting the duration. Before birth there is infinity, represented in one of the two external circles, and between the two circles we have the duration of everything. Everything is born and dies. The same way the image we see in a mirror appears and disappears: it wasn’t there – it’s there – it’s not there anymore.

We therefore are born and die constantly. Through the trinamic symbol, we illustrate the fact that in the two external circles we have infinity: the time before we are born and after we have died respectively; in the middle is the duration, inscribed in the continuum of birth and death. Duration is dynamic, not static.

Duration means a time in which matter generates and regenerates in a way to develop a consistency that organises and consumes itself within a time span. Everything that is part of universe has a duration, even stars are born and die… this is a fact that nothing and nobody can escape. We last as long as nature allows us to and we must take care of the time we spend on this planet. The Third Paradise represents our ability to regenerate ourselves as long as we can, both individually and socially.

In 2013 you produced the mirror painting ‘Ritratto Celant. Germano, Paris, Argento’, portraying Germano, his wife Paris Murray and their son Argento. What did it mean for you, as an artist, to create a work dedicated to your curator and his family?

This work expresses my fondness for him, and it was for me important to include his wife Paris and their son Argento in this relationship. Germano won’t ever be able to see himself in this mirror painting again, but he will be present in the lives of Paris and Argento through the image, which will keep his memory alive.

Michelangelo, you and Celant were also similar in appearance: always wearing black. Is there a reason behind this choice of colour?

In the 1960s, I used to dress in clothes of different colours, as if I were wearing the costumes of the world. In 1969, though, I wrote a text titled ‘L’uomo nero’ (The black man, published by Marcello Rumma in March 1970), about myself and the Zoo. The black man represents the joining element that would develop into the symbol of the Third Paradise. The reference is to that black I’ve recently defined as ‘the empty space’, the same we see among the stars. This is why I’ve worn black since, but Celant would have had his reasons for it.

Germano Celant with Michelangelo Pistoletto’s work Struttura per parlare in piedi (Structure for Talking while Standing). Picture taken at the Luhring Augustine Gallery in New York on the occasion of the 2013 exhibition ‘Michelangelo Pistoletto. The Minus Object 1965-1966’. Photo credits: Pierluigi Di Pietro.

What did Germano Celant leave to art?

From a personal point of view, I’d say that his legacy to art is Arte Povera. He couldn’t of course limit himself to this though, and he continued working on an international scale by supporting the best works. In addition to that, he had recently curated extremely important exhibitions like, for example, ‘Art & Food’ at Triennale di Milano, organised on the occasion of Expo 2015. This exhibition was of great significance because it connected the whole history of art with contemporary art; and in producing it, Germano showed all the knowledge, wisdom and capability of a curator of the highest calibre. A curator-creator, I’d say. Fundamental was also the exhibition ‘Post Zang Tumb Tuuum. Art Life Politics: Italia 1918–1943’, which he curated for Fondazione Prada: its tremendously innovative concept presented works from the past in historical spaces virtually reproduced. A testimony to his totally revolutionary curatorship skills.

What would you tell him if you had the opportunity to talk to him one last time?

Rather than talking to him, I would keep working with him on the two projects we had started, that is a monograph and a reasoned catalogue, which will have to be abandoned. Since Celant can’t hear me anymore, I’d like to say something to his wife and son, though: I wish them the very best for a life that will undoubtedly carry on making the most of Germano’s teachings and exemplar behaviours.